SATURDAY Oct. 26 (HealthDay News) — Many poorer patients with the autoimmune disease lupus don’t take their medications as prescribed, a new U.S. study suggests.

Researchers found that lupus patients on Medicaid — the public health insurance program for the poor — were often not sticking with their prescriptions. Over six months, patients picked up enough medication to cover only 31 percent to 57 percent of those days.

The findings are concerning, experts say, not only because lupus drugs can help send symptoms into remission, but because they may also stave off some of the long-term consequences of the disease.

“It’s alarming,” said lead researcher Dr. Jinoos Yazdany, of the University of California, San Francisco. “These medications have a proven track record of improving patients’ outcomes.”

The study used pharmacy claims data, so it’s not possible to say why people were not taking their medication as prescribed, Yazdany said.

But money could be one factor. Medicaid covers the drugs, Yazdany noted, but even a small co-pay could be a barrier for low-income patients.

Drug side effects could be another issue, Yazdany said, as could a lack of education about the medications. “Some people may not be fully aware of the benefits of these drugs,” she said.

Yazdany is scheduled to present the findings Saturday, at the American College of Rheumatology’s annual meeting in San Diego.

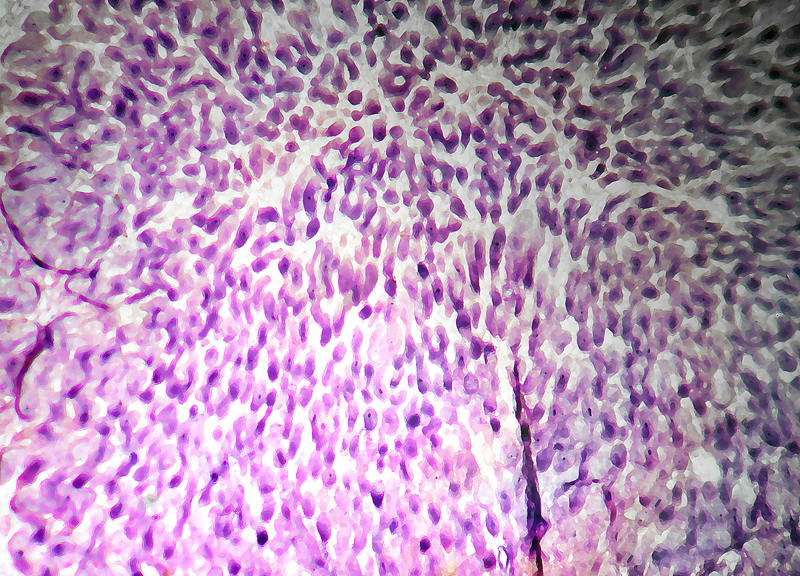

The most common form of lupus is systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In SLE, the immune system attacks the body’s own tissue, damaging the skin, joints, heart, lungs, kidneys and brain.

The disease mostly strikes women, usually starting in their 20s or 30s.

Lupus drugs include immune-system suppressors, such as cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) and tacrolimus (Prograf), and anti-malaria drugs, such as hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil), which can ease the fatigue, joint pain and skin rash seen in lupus.

Part of the goal is to control symptom flare-ups, including fatigue, fever, joint pain and skin rash. But the drugs can also reduce organ damage that can lead to kidney failure and heart disease.

The study included 23,187 Medicaid patients, mostly women, who were prescribed at least one drug for lupus. Yazdany’s team used pharmacy claims to gauge whether patients were sticking with their prescribed regimen.

In general, patients lacked medication for a substantial proportion of the six months. But black, Hispanic and Native American patients were less compliant than white and Asian patients — with only enough medication to cover a little more than half of the time period. And people living in the Midwest were less compliant than residents of other regions.

Overall, fewer than one-third of all patients had enough medication to cover at least 80 percent of the study period.

Dr. Cristina Drenkard, an assistant professor at Emory School of Medicine in Atlanta, said this finding is “very concerning.”

Low-income minorities with lupus are known to fare worse than their white counterparts, and the reasons are probably many, noted Drenkard, whose research focuses on lupus. But it’s likely that lesser adherence to drug regimens is one reason, she said.

Drenkard and her colleagues recently published a small study looking at whether a “self-management” program could help low-income black women with lupus. And they found that women who attended workshops at a public clinic were feeling better and doing a better job of taking their medication and generally managing their disease.

“We think self-management support like this is important for people with SLE,” Drenkard said.

Still, a program like that would be only one part of the solution, these experts added.

“We need more research to understand what the barriers are to drug adherence, from the patient point of view,” Yazdany said.

Another study to be reported at the same meeting underscores the importance of sticking with prescriptions. Researchers found that among more than 1,700 lupus patients in 11 countries, those taking anti-malaria drugs were less likely to show damage to their kidneys, heart or other organs over six years.

Do lupus patients with private insurance do a better job of sticking with their medications? It’s not clear, said Yazdany. With Medicaid, there are state databases to comb through, but there is no similar way to study lupus patients with private insurance on a national level.

For now, Yazdany said it’s important for all lupus patients to bring any medication concerns to their doctor. If side effects are an issue, she said, your doctor may be able to adjust the dose or switch the medication.

“We have more [drug] options available now than we used to,” Yazdany said. “So there’s a good chance that something else will work for you.”

Data and conclusions presented at meetings are typically considered preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed medical journal.

More information

The Lupus Foundation of America answers common questions about this autoimmune disease.

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.