MONDAY, June 9, 2014 (HealthDay News) — Older men taking the cholesterol-lowering drugs known as statins appear to be slightly less active than those who don’t take them, a new study suggests.

Statin users logged about 40 fewer minutes of moderate activity each week compared to nonusers, according to the study. These findings confirm those of previous studies that found an association between a drop in activity and the use of statin medications such as Lipitor, Pravachol, Crestor, Zocor, Lescol and Vytorin, according to background information in the study.

However, the study’s conclusions don’t mean that people should abandon their cholesterol-lowering medications.

“Statins are extremely helpful for people who need them,” stressed study lead author David Lee, an assistant professor in the department of pharmacy practice at Oregon State University/Oregon Health and Science University’s College of Pharmacy in Portland. “They’ve really changed the landscape of cardiovascular health over the last 20 years.”

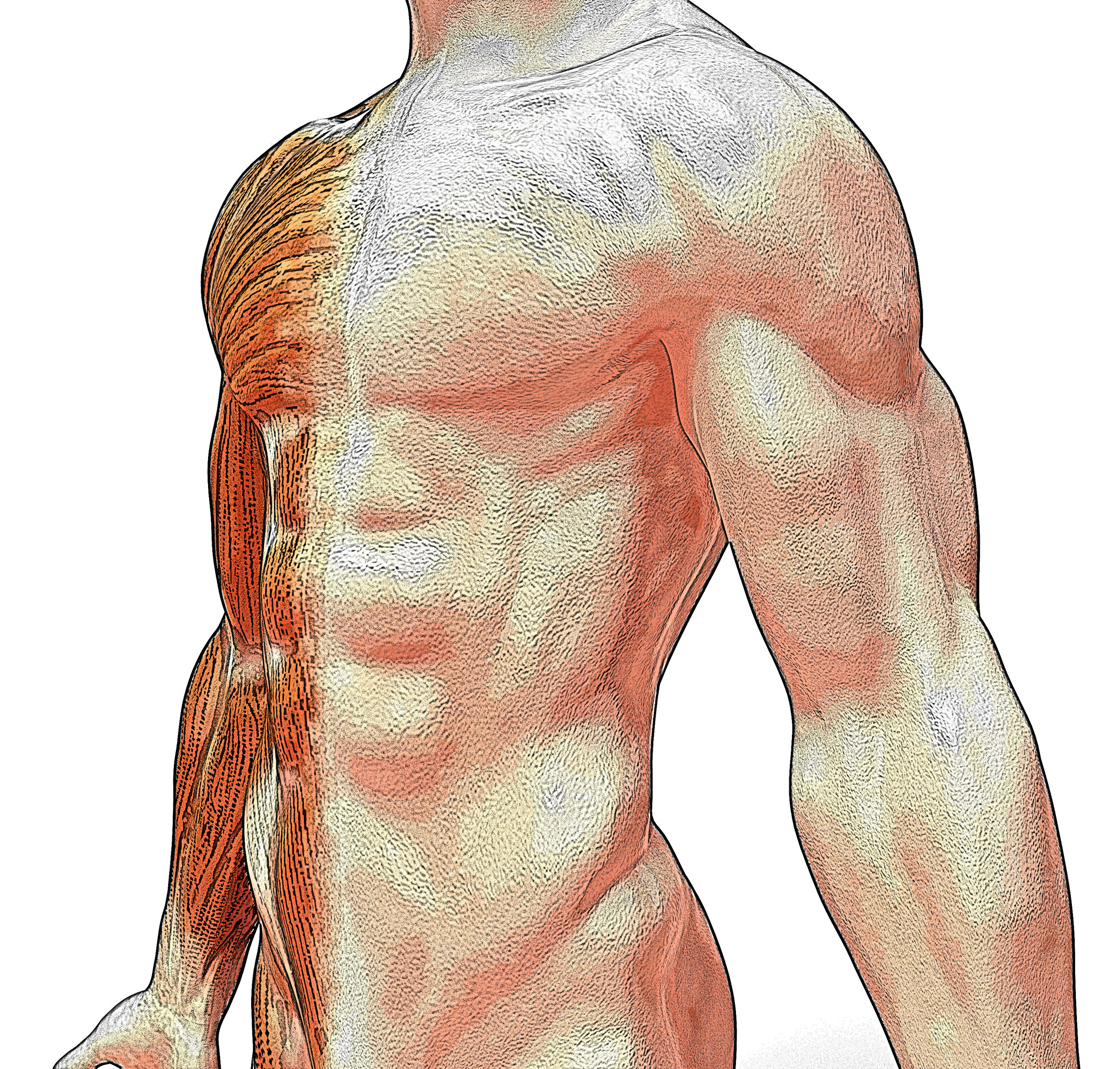

“But the thing I want people to be aware of is that they can have some adverse effects on muscles that might lead to a decrease in exercise,” Lee continued. “Because by being aware of that problem perhaps we can encourage patients to actually make an effort to push themselves to maintain their exercise habits. Because exercise is really very important, both for maintaining general health and for maintaining the ability to carry on independently as we age.”

Lee and his colleagues report their findings in the June 9 online issue of JAMA Internal Medicine.

Statins are generally considered to be a safe way to reduce bad cholesterol levels and lower the risk for plaque build-up in blood vessels and subsequent heart disease, according to the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). Side effects may include muscle pain, fatigue and weakness, according to the study.

To explore how statins might affect physical activity among older men, the study authors analyzed data on more than 3,000 men aged 65 and older recruited between 2000 and 2002.

The average age was 73. All of the men were able to walk on their own and live independently.

About a quarter were already taking statins when the study launched, while roughly another quarter began using statins at some point during a seven-year follow-up period. About half never took statins.

All participants offered details on their physical activity routines at the start of the study, and then again twice more over the years. In addition, at the time of their third and final report, all spent a week wearing a movement-monitoring device called an accelerometer to track moderate and vigorous physical activity levels, as well as time spent being sedentary.

The team found that based on survey responses, activity levels appeared to decline slightly among both statin users and nonusers.

However, men who newly embarked on a statin regimen during the study experienced a faster rate of activity decline than those who never took statins.

What’s more, even after accounting for other factors such as a prior history of heart attack and/or stroke, the accelerometer readings revealed that both moderate and vigorous activity levels were measurably lower among statin users.

For example, statin patients engaged in five-plus fewer minutes of moderate activity, and 0.6 fewer minutes of vigorous activity, on a daily basis. At the same time, their sedentary habits rose by nearly eight minutes a day, according to the study.

“Now, we didn’t look at the underlying cause or reason for decreased exercise,” Lee acknowledged. “But the main hypothesis is that people who take a statin do experience an increase in muscle pain. It’s actually the most common side effect. And observational studies have shown that as many as 20 percent of people taking statins will have muscle pain.”

“At the same time, weakness and fatigue are also side effects,” he noted. “And they could also be a part of the problem. It could be a combination of feeling a little bit of pain, feeling a little more tired, and feeling a little bit weaker. All of that together might be why patients are just not willing to do as much exercise. It could also perhaps be that other people who are on statins think they don’t need to exercise anymore, as well. But to be honest, I don’t think that’s really the biggest factor. I think it’s more to do with the side effects.”

In an editorial accompanying Lee’s study, Dr. Beatrice Alexandra Golomb, a professor of medicine at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine in La Jolla, said that the potential impact of statins on exercise patterns is something that “physicians and patients alike should bring into the discussion when assessing how these drugs may affect a patient’s overall quality of life.”

“Over the course of one day the drop in activity may seem small,” she noted. “But over time it really adds up, particularly when most people are already shortchanging themselves in terms of the amount of exercise they need. We know that exercise has profound benefits for people in virtually every aspect of health, particularly in older age.”

“So this is not to say that people who clearly merit statin therapy shouldn’t take it,” Golomb stressed. “For many, the benefits will surpass these sorts of considerations. But there are many people on the margins for whom this medication’s impact on exercise is an issue worth discussing.”

More Information

For more information on statins, visit the U.S. National Institutes for Health.

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.