WEDNESDAY, Feb. 5, 2014 (HealthDay News) — Obese people who are considering weight-loss surgery should choose their procedure carefully if they hope to be free of chronic heartburn, a new study suggests.

The study of nearly 39,000 patients found that while traditional gastric bypass procedures reduced heartburn and acid reflux symptoms in most sufferers, a newer procedure — called a laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy — was largely unhelpful for those who already had gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD. What’s more, about 1 in 11 people who didn’t have GERD before sleeve gastrectomy developed the condition after their procedure.

The study was published Feb. 5 in the journal JAMA Surgery.

“The fact that this surgery is contributing to reflux is a bit of a wake-up call that we need to at least be a little bit more selective in who is a good candidate for sleeve gastrectomy,” said Dr. John Lipham, an associate professor of surgery at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine in Los Angeles. He specializes in treating GERD and diseases of the upper gastrointestinal tract, but was not involved in the current research.

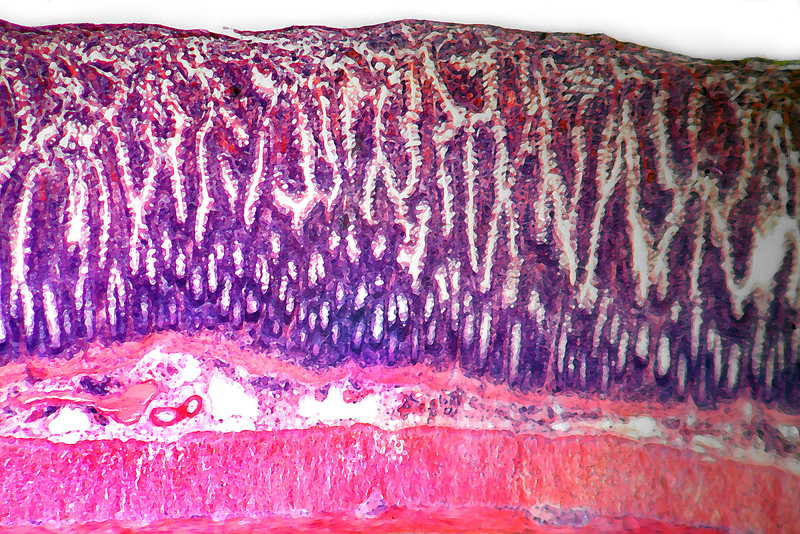

GERD is the backflow of stomach contents into the esophagus, the tube that carries food from the mouth to the stomach. Obesity more than triples the risk for the condition in men, experts say. Obese women face six times the risk.

The backwash of stomach acid and other digestive juices causes heartburn and acid reflux, a burning sensation in the chest and throat. Doctors diagnose GERD when a person has episodes of heartburn at least twice a week or when symptoms interfere with daily life.

The condition isn’t merely uncomfortable. Chronic exposure to stomach acid can change the cells lining the esophagus. This can lead to a range of problems from scar tissue that makes it difficult to swallow to cancer.

“The fact of the matter is [GERD] is a serious medical condition and it can lead to a lot of complications,” Lipham said.

“Don’t get me wrong, I think the sleeve gastrectomy is a good procedure, but it seems best for selected patients without a significant GERD history,” he added.

For the study, researchers reviewed the cases of patients who had weight-loss surgery between 2007 and 2010. More than 4,800 patients had sleeve gastrectomies over that period, while nearly 34,000 had gastric bypass procedures.

In a gastric bypass, surgeons make a pouch at the top of the stomach that holds about a cup of food. That pouch is then attached directly to the middle portion of the small intestine, rerouting food past the first section of the gut.

In a sleeve gastrectomy, surgeons remove more than 85 percent of the stomach and shape the remainder into a sleeve or tube, but they don’t alter how the food travels through the gut. Weight loss with sleeve gastrectomy is generally slower than gastric bypass, and for some patients, this procedure is the first step before a full bypass.

The average age of patients in the study was 46. Nearly three-quarters of patients in both groups were women, and the average body mass index (BMI) for both groups was 48 before surgery, suggesting that each group had similar amounts of weight to lose.

Before surgery, 45 percent of the sleeve gastrectomy group and 50 percent of the gastric bypass group had GERD.

After surgery, the picture changed.

Among those who had sleeve gastrectomies, nearly 84 percent of GERD sufferers said they still had symptoms six months or more after their procedures, while 16 percent said their symptoms had resolved. Nine percent said their symptoms got worse, the study found.

After gastric bypass, however, 63 percent of GERD sufferers saw complete resolution of their symptoms at least six months after surgery. GERD symptoms stabilized in 18 percent of patients, while 2.2 percent saw their symptoms worsen.

What’s more, within the group that went into surgery untroubled by heartburn, 9 percent developed GERD after their sleeve gastrectomy.

GERD after weight-loss surgery was linked to having more complications overall. And for sleeve gastrectomy patients, it was also linked to the failure to lose at least 50 percent of body weight over the next year.

“Bariatric surgery isn’t one-operation-fits-all. It really needs to be tailored to the patient,” said study author Dr. Matthew Martin, a surgeon at Madigan Army Medical Center in Tacoma, Wash.

Martin said shape probably accounted for the differences in GERD symptoms after surgery. With the sleeve, the stomach becomes a tube, which offers more resistance to food passing through than the rounder pouch created by the bypass.

“Somebody who has significant reflux symptoms, or GERD, a sleeve may not be the best option for them, and it’s certainly something that needs to be discussed before surgery,” he said.

More information

Visit the American Gastroenterological Association for more information on obesity and its treatments.

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.