WEDNESDAY, Dec. 3, 2014 (HealthDay News) — Researchers say they’ve honed in on the possible genetic cause of a rare condition called gigantism that causes excessive growth in children.

“Gigantism is a disease in childhood that characterized by excessive growth, resulting from an excess of growth hormone production” by the pituitary gland, explained Dr. Patricia Vuguin, a pediatric endocrinologist at Cohen Children’s Medical Center in New Hyde Park, NY.

“In adult patients, the same condition is called acromegaly,” said Vuguin, who was not involved in the new study.

According to researchers at the U.S. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), some people with gigantism have a tumor in the pituitary gland that secretes extra hormone, while others have an oversized pituitary. People with gigantism typically grow rapidly, are abnormally tall with large hands and feet, and may have delays in puberty.

Gigantism is often treated by removing the tumor or the entire pituitary, but can be treated with medication alone in some cases, the research team said.

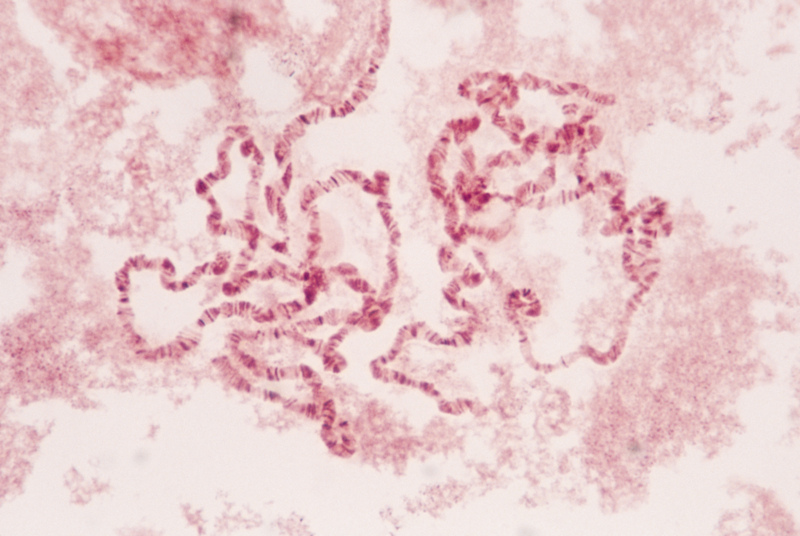

The new study found that duplication of a short stretch of the X chromosome is associated with the rare disorder, and that a single gene within that region has a major impact on how much children grow.

The study was led by Dr. Constantine Stratakis, director of the division of intramural research at NICHD. The research began with a family who came to the the U.S. National Institutes of Health for treatment for gigantism in the mid-1990s. In that family, the mother and two of her sons all had the condition.

“Giants are very rare. If you have three cases in the same family, that is very rare,” Stratakis said. A second family from Australia with an affected daughter also looked for treatment, and tests showed certain genetic similarities between all of the patients.

In total, Stratakis’ team studied 43 people who had gigantism as an infant or toddler. The research revealed that they all had the duplication of the same section of their X chromosome.

On the other hand, family members without gigantism did not have this duplication, Stratakis’ group found.

Further investigation also revealed that the same four genes were duplicated in all of the gigantism patients. After testing the four genes, the researchers zeroed in on the most likely suspect, a gene called GPR101. Its activity was up to 1,000 times stronger in the pituitaries of patients with the duplication than in the pituitaries of normally developing youngsters, Stratakis’ team said.

“We believe GPR101 is a major regulator of growth,” Stratakis said in an NICHD news release.

The researchers believe the findings could lead to new treatments for gigantism. It might even help improve understanding about the opposite condition — undergrowth — in children, which is currently treated by giving patients growth hormone.

“Finding the gene responsible for childhood overgrowth would be very helpful, but the much wider question is what regulates growth,” Stratakis said.

In theory, excessive or inadequate growth in children are probably controlled by the same mechanisms, he explained.

“As pediatricians and endocrinologists, we look at growth as one of the hallmarks of childhood. Understanding how children grow is extraordinarily important, as an indicator of their general health and their future well-being,” Stratakis said.

Vuguin believes the new findings hold real promise in curbing gigantism.

“Alterations of this gene are likely the cause the abnormal growth in very young children with gigantism, as well as the growth of pituitary tumors in adult patients with acromegaly,” she said.

More information

The U.S. National Library of Medicine has more about gigantism.

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.