WEDNESDAY, July 30, 2014 (HealthDay News) —

Although the vast majority of kids with autism have abnormal sensory behaviors, their brains are still wired very differently from children who have trouble processing sensory stimuli, researchers report.

Children with sensory processing disorders (SPD) can be overly sensitive to sound, sight and touch. They can also have poor motor skills and show a lack of concentration.

Complicating matters, some kids with SPD have more severe symptoms than others. Some have trouble tolerating loud noises, like a vacuum. Others can’t hold a pencil or control their emotions. Symptoms can also vary from one day to the next. This had led to a debate about whether SPD should be considered a separate disorder, the researchers pointed out.

These kids “often don’t get supportive services at school or in the community because SPD is not yet a recognized condition,” study corresponding author Dr. Elysa Marco, a cognitive and behavioral child neurologist at Benioff Children’s Hospital San Francisco at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), said in a university news release. “We are starting to catch up with what parents already knew; sensory challenges are real and can be measured both in the lab and the real world.”

“With more than 1 percent of children in the United States diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder, and reports of 5 to 16 percent of children having sensory processing difficulties, it’s essential we define the neural underpinnings of these conditions, and identify the areas they overlap and where they are very distinct,” study senior author Dr. Pratik Mukherjee, a professor of radiology and biomedical imaging and bioengineering at UCSF, said in a university news release.

In conducting the study, published online July 30 in the journal PLOS ONE, the researchers compared the brains of 16 boys with SPD and 15 boys with autism. All of the boys were between the ages of 8 and 12. These patients were compared to 23 boys who were developing normally.

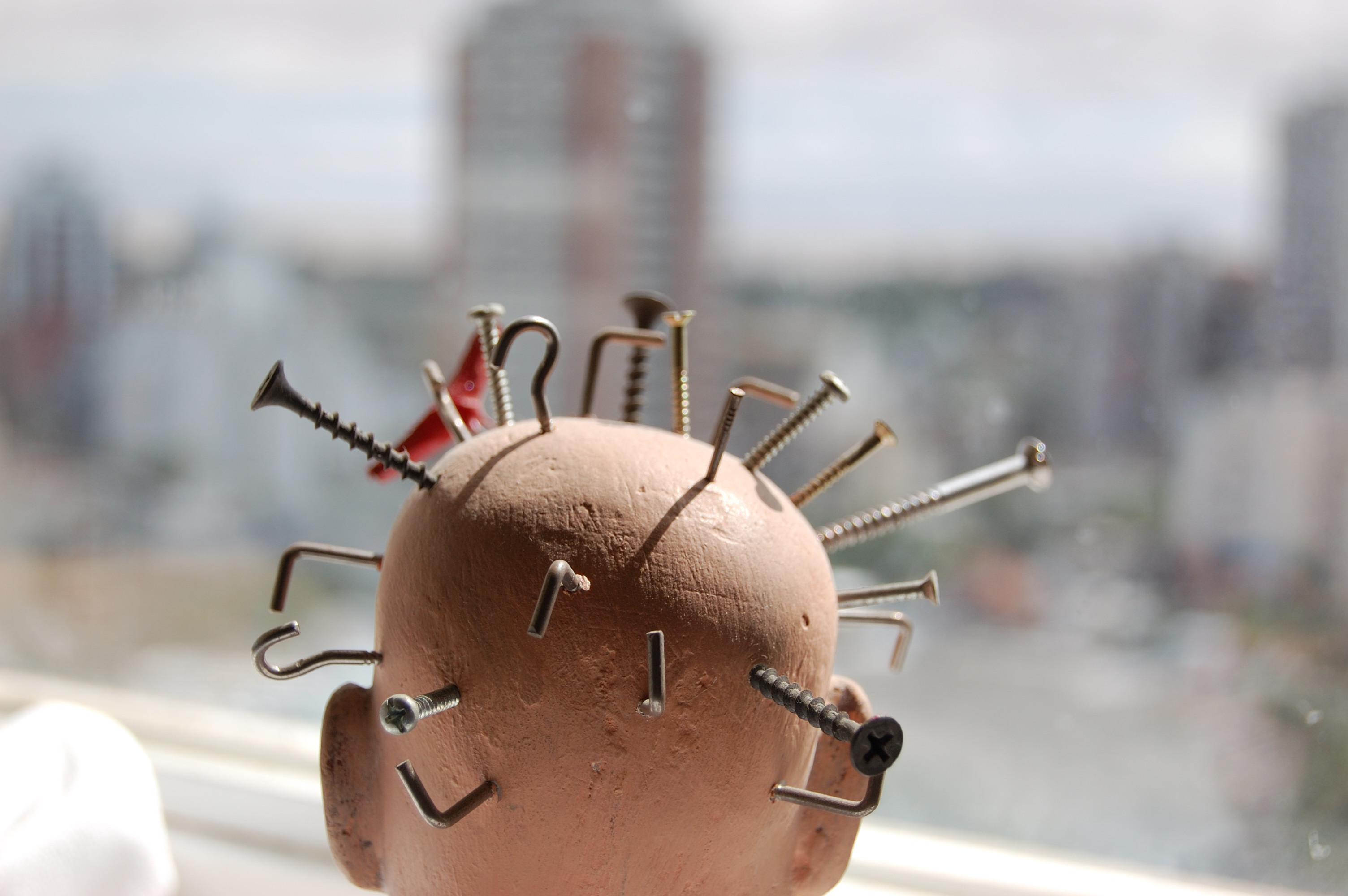

Using an advanced form of MRI, the researchers were able to examine white matter, the “wiring” that links different areas of the brain.

The boys with SPD and autism had reduced connectivity in certain areas of the brain involved in basic sensory information. However, only the boys with autism had impairment in specific parts of the brain essential for social-emotional processing.

“One of the classic features of autism is decreased eye-to-eye gaze, and the decreased ability to read facial emotions,” noted Marco. “The impairment in this specific brain connectivity not only differentiates the autism group from the SPD group but reflects the difficulties patients with autism have in the real world. In our work, the more these regions are disconnected, the more challenge they are having with social skills.”

Meanwhile, children with SPD had less connectivity in the tracts of the brain involved in sensory processing.

“One of the most striking new findings is that the children with SPD show even greater brain disconnection than the kids with a full autism diagnosis in some sensory-based tracts,” noted Marco. “If we can start by measuring a child’s brain connectivity and seeing how it is playing out in a child’s functional ability, we can then use that measure as a metric for success in our interventions and see if the connectivities are changing based on our clinical interventions.”

More information

The U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke provides more information on autism.

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.