MONDAY, March 24, 2014 (HealthDay News) — A new wireless pacemaker appears safe and feasible for use, potentially advancing the technology that cardiologists use to maintain heart rhythm in patients, according to results from a new clinical trial.

Doctors successfully implanted the device in 32 out of 33 patients. Of these, two people who received the pacemaker developed side effects — a complication-free rate of 94 percent. Complications for the patient with unsuccessful implantation, however, proved to be severe.

After three months, the new pacemakers continued to function well, the researchers reported in the April 8 issue of the journal Circulation. They expect to report longer-term outcomes later this year.

The concept of a self-contained wireless pacemaker has been around more than 40 years, and this first successful use of such a device to treat humans is considered a step forward for cardiology.

“This is an advance that will have a huge impact on the field,” said Dr. Bradley Knight, a cardiologist at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and a spokesman for the American Heart Association. “This opens up a whole bunch of new potential opportunities for pacing a patient’s heart.”

Today’s pacemakers maintain the heart’s rhythm by sending electrical signals through wires that run from the device into the heart through a person’s veins, said the study’s lead author, Dr. Vivek Reddy, director of the cardiac arrhythmia service at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City.

“These leads are the weak link for the whole system,” Reddy said of the wires. The leads tend to break over time, and when they do doctors must extract and replace them.

Unfortunately, the wires sometimes grow into the wall of the vein, and laser surgery could be required to cut them free.

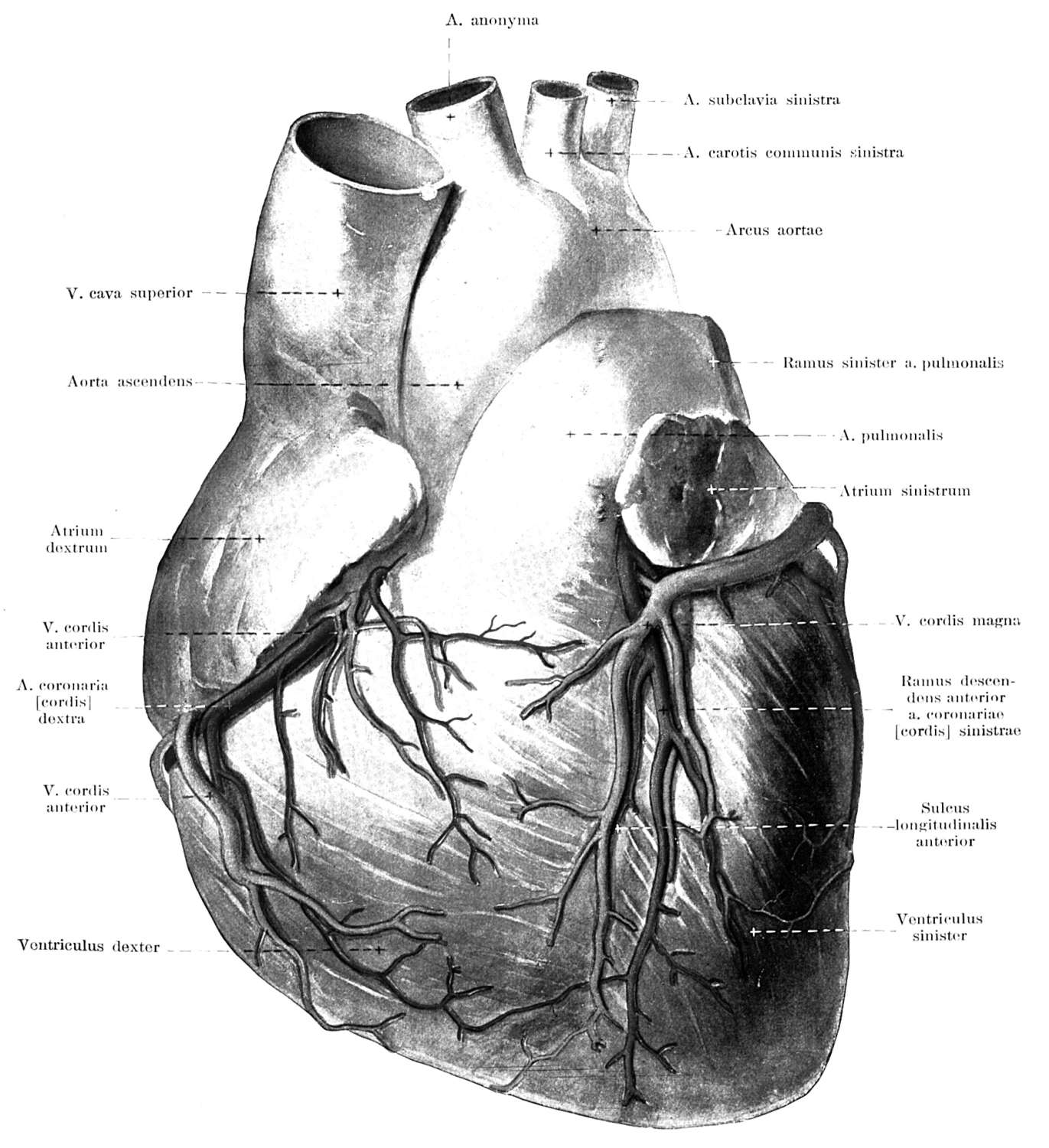

This new wireless pacemaker contains its own pulse generator, and is affixed directly inside the right ventricle of the heart through a catheter run up a vein from a patient’s leg or groin, Reddy said. The nonsurgical procedure is faster and easier than the surgery currently required to implant a pacemaker, the researchers said.

The unit itself is smaller than a triple-A battery — 6 millimeters in diameter and about 42 millimeters long. “The total amount of space it displaces is about 1 cc of fluid, so it’s very, very small,” Reddy said.

The wireless pacemaker is expected to operate for eight to 14 years before it runs out of juice, Reddy said.

The pacemaker is manufactured by Nanostim Inc., of Sunnyvale, Calif. The study was funded by Nanostim, which, according to the study, employs two of the researchers and has provided several more with grant support. Reddy also has stock options in the company.

The clinical trial for the device involved 33 patients at two hospitals in Prague and one in Amsterdam. The average age of the patients was 77, and two-thirds were men.

One patient experienced complications during the implant procedure, and this case highlights one of the potential problems with the new pacemaker, Reddy and Knight said.

Since the device must be placed inside the heart, there is a risk that the heart muscle can be torn during the procedure. That’s what happened to the 33rd patient, who underwent emergency surgery to repair the tear but later died after suffering a stroke.

Two patients who successfully received the implant later developed complications.

In one patient, the pacemaker drifted into another heart chamber through a hole in the person’s heart wall left by a birth defect. Doctors discovered the problem, removed the device in about six minutes and replaced it with another wireless pacemaker, according to the study.

The second patient with complications experienced fainting and rapid heart beat, and doctors ended up replacing the pacemaker with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

Also, the pacemaker initially would be of limited use in the United States because it can only provide pacing to one chamber of the heart. Between 75 percent and 80 percent of patients in the United States need pacemakers that help control the rhythm of both the upper and lower chambers of their heart, Reddy said.

This wireless pacemaker would at first be useful in treating people who have atrial fibrillation — an irregular heartbeat — since they need pacing only in their right ventricle, Knight said. It also could help people with less severe heart problems who need only intermittent pacing.

Knight said he believes problems related to heart tears and single-chamber pacing will be resolved as newer, smaller models of wireless pacemaker become available.

“This is just the beginning,” he said. “These things will get smaller and be able to be placed in multiple locations in the heart.”

For example, dual-chamber pacemaking could be achieved using a pair of the wireless devices — one in the upper atrial chamber and another in the lower ventricular chamber — if communication is established between them to sync their pulses.

Clinical trials for the device already have begun in the United States, Reddy said. The first American received a wireless pacemaker about a month ago at Mount Sinai Hospital.

Researchers hope the device can receive approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration by 2016. The wireless pacemaker currently is available to patients outside the United States, Reddy said.

The medical device firm Medtronic has developed a competing wireless pacemaker, Reddy said, and clinical trials for that device started in late 2013.

Because of the competition, Reddy expects that the new pacemakers will be more expensive than current devices but not exorbitantly so.

“I’m sure they’ll charge a premium in the beginning, but if there’s any competition they can’t charge too much more,” he said.

More information

For more about pacemakers, visit the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.