MONDAY, April 27, 2015 (HealthDay News) — Special MRI scans of the heart can help spot people with atrial fibrillation — a common heart rhythm disorder — who are at high risk for stroke, a new study shows.

The study also calls into question the mechanism linking atrial fibrillation with higher stroke risk, says a team reporting the findings April 27 in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

The irregular heartbeat can increase the risk of stroke, but it’s difficult to pinpoint which of the estimated 6 million Americans with atrial fibrillation are at high risk for stroke and should be put on blood-thinning drugs.

In the new study, a team led by Dr. Hiroshi Ashikaga, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, used special motion-tracking MRI scans on 169 patients with atrial fibrillation, aged 49 to 69. The test combined standard MRI scans with motion-tracking software that analyzes heart muscle movement, the team explained.

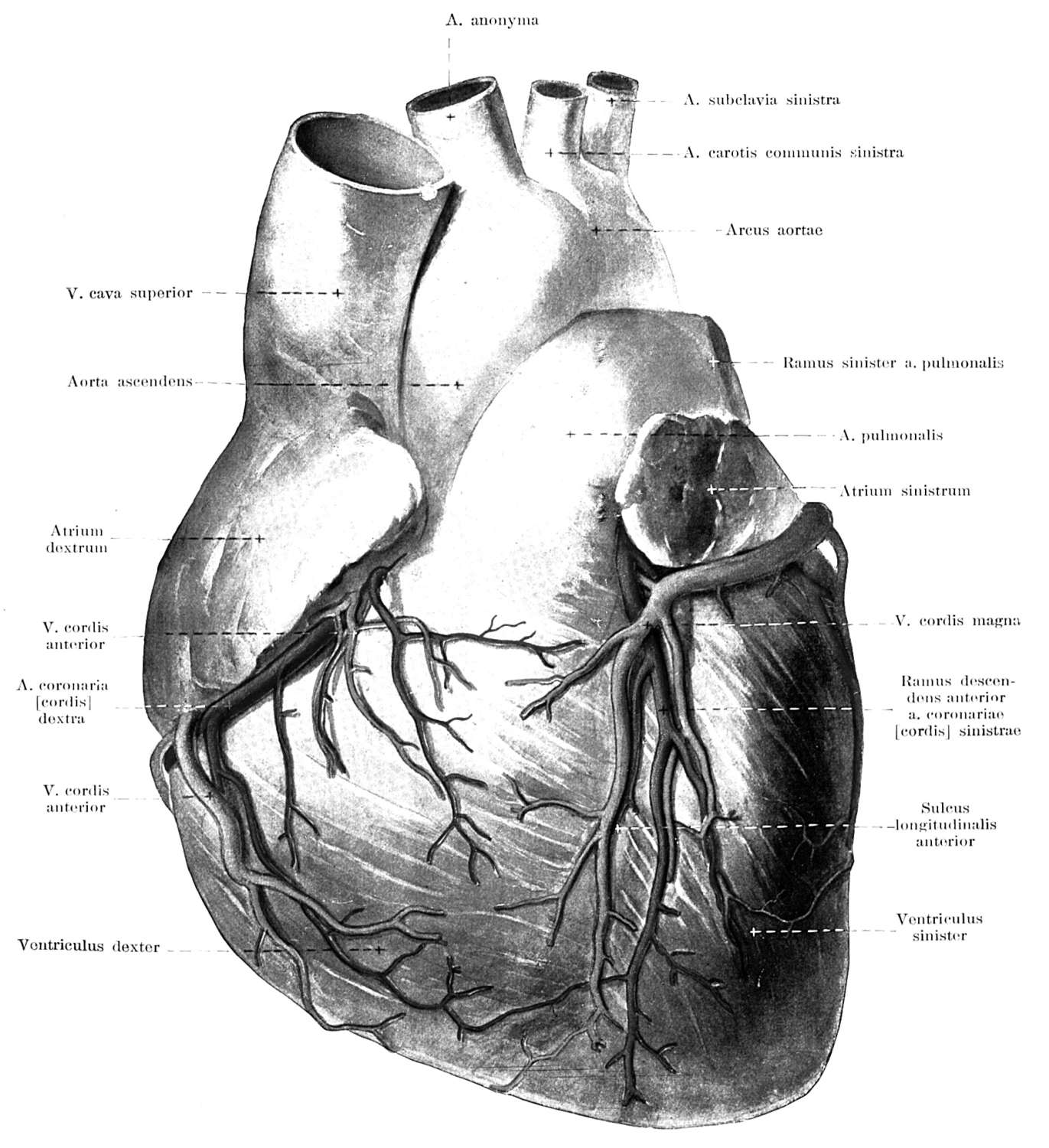

The study revealed that a specific alteration in the function of the left atrium — one of the heart’s four chambers — may be a sign of stroke risk.

“Our research suggests that certain features of the heart’s upper left chamber that are easily seen on heart MRI could be the smoking gun we need to tell apart low-risk from high-risk patients,” Ashikaga, an assistant professor of medicine and biomedical engineering at the school, said in a Hopkins news release.

Being able to identify atrial fibrillation patients at high risk for stroke is important, the researchers said, because it would help doctors weigh stroke risk against the serious side effects posed by prescribing blood thinners to reduce that risk.

It’s not clear why altered function in the left atrium increases stroke risk, but it may be linked to slower blood flow that increases the risk of blood clots that can lead to stroke, the researchers said.

“Altered function in the left atrium of the heart may lead to stroke independently of the heart rhythm disturbance itself,” explained Dr. Joao Lima, a professor of medicine and radiology at the medical school and director of cardiovascular imaging at Johns Hopkins Hospital. He and Ashikaga believe this altered heart chamber function could occur even in people without atrial fibrillation.

“Maybe when it comes to stroke risk and afib, we’ve been chasing the wrong guy all along,” Ashikaga said. “Maybe atrial fibrillation itself is not the real culprit and dysfunction of the left atrium is the real baddie. It’s a possibility we have to consider and will in an upcoming study.”

Other experts were intrigued by the finding.

Dr. Richard Hayes is a cardiologist at the Lenox Hill HealthPlex in New York City. He said that, as it stands now, the decision to give a patient with atrial fibrillation a blood thinner is made based on factors such as their age, other heart risk factors or prior history of stroke.

“But what if we were able to actually see the left atrium directly?,” Hayes said. He said that while the Hopkins findings look promising, “clearly this requires further study.” And he stressed that, “MRI is not readily available and is expensive. However, it may be quite useful in those patients whose risk of stroke is still unclear.”

Another expert agreed that the technology holds promise.

Cardiac MRI “now also appears to have the potential to predict which patients with atrial fibrillation will be at increased risk for a stroke,” said Dr. Juan Gaztanaga, director of advanced cardiac imaging at Winthrop-University Hospital in Mineola, N.Y.

If proven successful, the technology “would allow us to identify higher risk patients and treat them more aggressively, and at the same time not expose low risk patients to blood thinners,” he said.

More information

The U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute has more about atrial fibrillation.

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.