MONDAY, Aug. 26 (HealthDay News) — A new implantable defibrillator accurately detects abnormal heart rhythms and shocks the heart back into normal rhythm, yet has no wires touching the heart, new research shows.

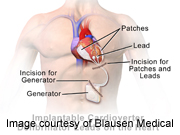

The device, called a subcutaneous implantable cardiac defibrillator (S-ICD), is placed under the patient’s skin and has a wire under the skin along the left side of the breast bone.

“The device detects life-threatening arrhythmias from normal rhythms, and once it notices the life-threatening rhythm it will automatically shock the heart back to its normal rhythm,” said lead researcher Dr. Martin Burke, director of the Heart Rhythm Center at the University of Chicago.

The advantage of the device is its durability — it lasts longer because there is not as much flexibility in the wiring, Burke said. Wires in standard implantable defibrillators need to be flexible to pass through blood vessels to the heart.

“This makes the system enticing for younger patients who have risk of cardiac arrest who currently don’t get standard systems because of [probable] failures of those systems over time,” Burke said. “The heart beats 30 million times a year, and those beats put wear and tear on those wires.”

The research was paid for by the device’s maker, Cameron Health Inc., and then by Boston Scientific Corp. after it acquired Cameron. The report was published online Aug. 27 in the journal Circulation.

Burke said the new device won’t replace standard implantable defibrillators because many patients who need an implantable defibrillator also need a pacemaker to keep the heart beating regularly and this new device does not pace the heart.

“It will, however, be a nice alternative for patients who don’t need pacing,” he said. The new device also can be used to replace a defective or worn out standard implantable defibrillator, he said.

The new device is a little more costly than standard implantable defibrillators, Burke said, with a price tag of about $24,000, compared with $18,000 to $22,000 for a standard implantable defibrillator.

The cost of the new device is covered by some insurance companies and Medicare, he added.

The S-ICD has been used in Europe and New Zealand since 2009 and was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2012, but long-term study is still required, the researchers said.

One expert said there’s a place for the new defibrillator.

“The subcutaneous defibrillator adds additional value for patients with indications for an implantable defibrillator who are poor candidates for standard systems,” said Dr. Leslie Saxon, chief of the division of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Southern California and author of an accompanying journal editorial.

Since the device is not a pacemaker, however, it doesn’t provide many options other devices do. “[Doctors should] think carefully about defibrillator selection and individualize patient care,” Saxon said.

Another expert said more clinical experience is needed to determine which patients will benefit most from its use.

“It is estimated that 200,000 to 400,000 people die suddenly every year in the United States, and the majority of these deaths are the result of the heart rhythm abnormalities ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation,” said Dr. Gregg Fonarow, a professor of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Although this study found the new device exceeded FDA-specified goals in terms of efficacy and safety, “additional studies with longer-term follow-up are needed to better define the effectiveness, safety and ideal patient population for this new device,” Fonarow added.

For the study, 314 patients using the device were evaluated over an average of six months. During that time, 21 patients had 38 episodes of ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia — abnormal rhythms that precede cardiac arrest. The average age of the patients was 52.

In each case, the device restored the heart to a normal rhythm, the researchers reported. Forty-one patients, however, received shocks when the heart wasn’t in a dangerous rhythm.

Ninety-nine percent of the patients had no complications from the device in the 180 days following implantation. In testing, the device recognized and reversed abnormal, life-threatening rhythms 100 percent of the time.

More information

For more on implantable defibrillators, visit the American Heart Association.

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.