WEDNESDAY, July 13, 2022 (HealthDay News) — About eight months after Ari Toumpas, a transgender woman, began the process of transitioning both socially and medically, she began to think about her voice.

A language teacher and graduate student at Ohio State University, Toumpas had been trying some vocal feminization exercises she had discovered online, but was not having success.

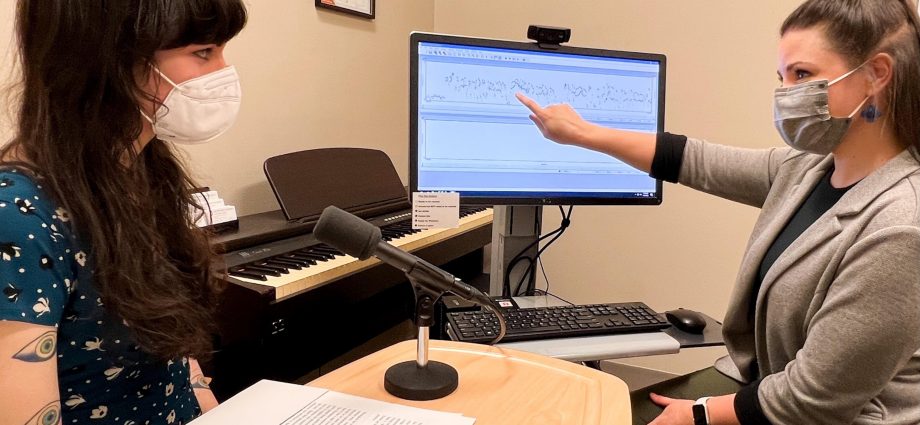

A referral from her primary care doctor led Toumpas to Anna Lichtenstein, a gender-affirming voice modification therapist at the university’s Wexner Medical Center, which offers a wide range of gender-affirming health care services.

“It’s been a process of just changing various little things and big things about my life to just make me feel more comfortable living as a human being with a body, and part of that was my voice,” said Toumpas, who is 25.

After 12 weeks of work with Lichtenstein and more practice at home, “I have a lot of comfort with my voice,” said Toumpas. “I know what I’m doing with it. It’s kind of effortless. I come to my voice each day when I wake up in the morning … I get in front of my class and I teach, and it’s comfortable.”

Voice modification is just one piece of gender-affirming care that can help transgender individuals feel more aligned with their bodies.

Lichtenstein said, “We use our voice throughout the day to communicate and as a speech pathologist all my training is in helping people to communicate within the world, with more confidence, more efficiently, feeling successful.”

Communication has a lot of gendered aspects to it, Lichtenstein noted, and the transgender, non-binary, gender-nonconforming patients who Lichtenstein sees in her work come to her for a variety of reasons and with an array of goals.

Some are seeking to not have people identify them as transgender in their community, sometimes because they’re concerned about safety. Others want a better sense of control and understanding of their voice. At the same time, some transgender people are not interested in vocal changes. They identify with how they sound, Lichtenstein said.

“But it is definitely within the scope of gender-affirming care, and it’s important because gender-affirming care in general can be really lifesaving for people, depending on where they live and what health care that they need or are seeking,” Lichtenstein said.

Speech language pathology and voice therapy is itself a very diverse field, encompassing everything from working with pediatric patients who need help with articulation and language fluency to adult patients in acute care as part of stroke recovery.

In Lichtenstein’s case, she gradually began adding more transgender adults and youths to her caseload before this work became her primary focus.

‘The voice is really personal’

“I really found this interest in providing gender-affirming care and wanted to be the very best, most competent provider that I could be in this area of health for this patient population,” Lichtenstein said.

Although Lichtenstein thinks it is not as common for speech therapists to focus on gender-affirming care, there are more speech therapists beginning this work around the United States by adding transgender patients to their existing caseloads.

Graduate programs are now more commonly offering curriculum that includes gender-affirming voice therapy. Specialty trainings also exist for professionals, she added.

It’s rare, but possible, to pair voice therapy with surgery. Such surgery can shorten and change the shape of the vocal cords.

But first, the process for voice modification therapy begins with a meeting with a laryngologist to assess a patient’s vocal health.

The next meeting is with the speech pathologist, to talk about quality of life and goals.

After that, there are typically 10 (give or take a few) 30- to 45-minute sessions. Lichtenstein works with her patients on understanding and controlling airflow, inflection patterns, pitch, resonance and location of sound.

“I approach it with this scientific vocal health standpoint and work from sound level to word level to sentence level, to reading and conversation,” Lichtenstein said.

“And I provide a lot of support for the patients along the way,” Lichtenstein continued. “What we’re doing is really personal. The voice is really personal. It’s very tied to sense of self and sense of identity.”

Gender-affirming voice therapy is more frequently sought out by people who are trans-feminine than those who are trans-masculine, Lichtenstein noted.

The reason is because the testosterone taken to transition from feminine to masculine thickens the vocal cords, which can alter and lower the voice. That does not happen when taking female hormones such as progesterone and estrogen.

However, Lichtenstein does see trans-masculine patients who opt out of hormone therapy and want to learn how to use their changing voices or have other issues arise.

A matter of safety

For Toumpas, the decision to do voice therapy was both aesthetic and for safety reasons. She didn’t want to experience discrimination or abuse by transphobic people. Her goal was not to be in one of the higher-resonating ranges, but to sound like Greek female singers whose voices she admired.

“I had a lot of aesthetic thoughts about my gender and how I wanted to play with my voice and Anna was very cool in working on those things on the fly,” Toumpas said.

A lot of transgender and non-binary people have the shared experience of feeling like their bodies are not truly theirs, said Olivia Hunt, policy director for the National Center for Transgender Equality, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy organization that works to make the United States a safer and friendlier place for transgender people.

For many who pursue medical transition, aligning their body with how they view themselves is a crucial part of living their lives, Hunt said.

It’s a matter of dignity and self-actualization, but also an issue of personal safety, Hunt added.

The organization’s 2015 survey found that nearly half of all transgender people in America reported being discriminated against, harassed or treated with violence.

“Having other ways to protect yourself to not be outed, not have your transgender status revealed to people that you’re interacting with on a casual basis, it can be a safety concern because if your voice is outing you while you’re out at the store buying groceries that can lead to completely unnecessary harassment from total strangers who decided that they just want to make life difficult for the trans person,” Hunt said.

Hunt also noted that transgender individuals have higher than average unemployment rates, which can also mean lack of access to insurance or limited insurance, making it harder to pay for gender-affirming care, including voice therapy.

Lichtenstein said she always tries to ensure her patients have all the resources they need in place for other gender-affirming services they need, depending on where they’re at in their journey, as well as to help them navigate insurance.

She bills to insurance for her sessions, but how well the therapy is covered varies widely by plan and policies that insurance companies make about what care they’ll cover. That’s an issue the Ohio State team tries to change directly by approaching companies to offer presentations detailing the care and the need for it.

Proposed laws may also affect this type of health care for those who need it. Ohio, for example, has two bills proposed in its legislature that would affect the LGBTQ community, including one that would prevent transgender minors from accessing any gender-affirming health care if it passes.

“I have teenagers on my caseload who come to me for voice every week and they are who they say they are and all the health care services that they are seeking out are services that they need,” Lichtenstein said. “So, I think it is very scary that that could potentially become something that is illegal in Ohio.”

More information

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association has more on gender-affirming voice therapy.

SOURCES: Anna Lichtenstein, MA, speech language pathologist and gender-affirming voice modification therapist, department of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery, Ohio State University’s Wexner Medical Center, Columbus; Olivia Hunt, JD, policy director, National Center for Transgender Equality, Washington D.C.; Ari Toumpas, BA, graduate student and teacher, Ohio State University, Columbus

Was this page helpful?

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.